Transmission and Emission Spectroscopy

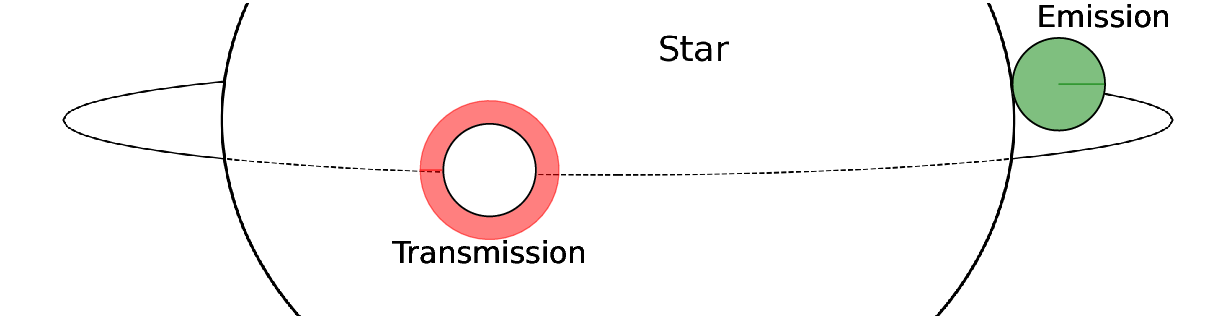

The most common method by which we observe the atmospheres of exoplanets is the transit method. This can be sub-divided into two categories, transmission and emission. In transmission, the planet is passing in front of the host star as observed by us, and the star's light will shine through the atmosphere, leaving an imprint of its chemical signature in the observed spectrum. At certain wavelengths where the chemical species in the atmosphere absorb strongly, the atmosphere is opaque and the planet's absorption is increased. By observing a range of different wavelengths, we can determine the chemical composition of the atmosphere.

In emission, we observe the planet just before it goes behind it's host star. By subtracting off the stellar flux as the planet goes behind the star, we can determine the emergent spectrum from the dayside of the planet. Emission geometries are particularly conducive to determining the temperature structure of the atmosphere, but generally we have to use infrared observations as it is these wavelengths where the planet is a little brighter to discern it from the very bright host star.

You can find some of my recent publications on transiting exoplanets below.

Trends in Chemistry, Rain-out, Ionization, and Atmospheric Dynamics of 6 ultra-hot Jupiters

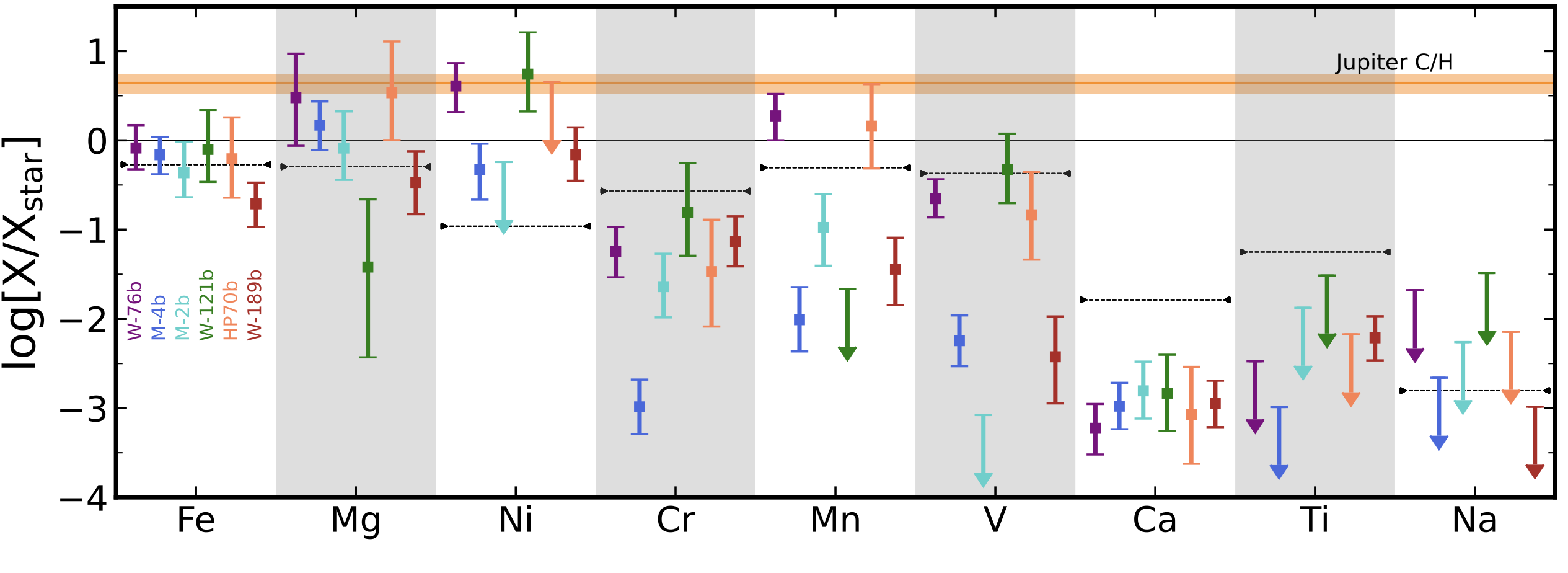

Ground-based high-resolution spectroscopy has detected numerous chemical species and atmospheric dynamics in exoplanets, most notably ultra-hot Jupiters. However, quantitative estimates on abundances have been challenging but are essential for accurate comparative characterization and to determine formation scenarios. I have retrieved the atmospheres of six planets (WASP-76 b, MASCARA-4 b, MASCARA-2 b, WASP-121 b, HAT-P-70 b, and WASP-189 b) with ESPRESSO and HARPS-N/HARPS observations, exploring trends in eleven neutral species and dynamics. While Fe abundances agree well with stellar values, Mg, Ni, Cr, Mn, and V show more variation, highlighting the rich diversity in chemistry of exoplanets. We find that Ca, Na, Ti, and TiO are underabundant, potentially due to ionization and/or nightside rain-out. We additionally constrain dynamics for our sample through Doppler shifts and broadening of the planetary signals during the primary eclipse, with blueshifts between ~0.9 and 9.0 km/s due to day-night winds. The precision of the observations also allows us to place constraints on the masses of two of the planets, MASCARA-2 b and HAT-P-70 b, where only upper limits have so far been available. This work has been published in The Astronomical Journal and can be found here.

Modelling Cloudy Exoplanets at High Spectral Resolution

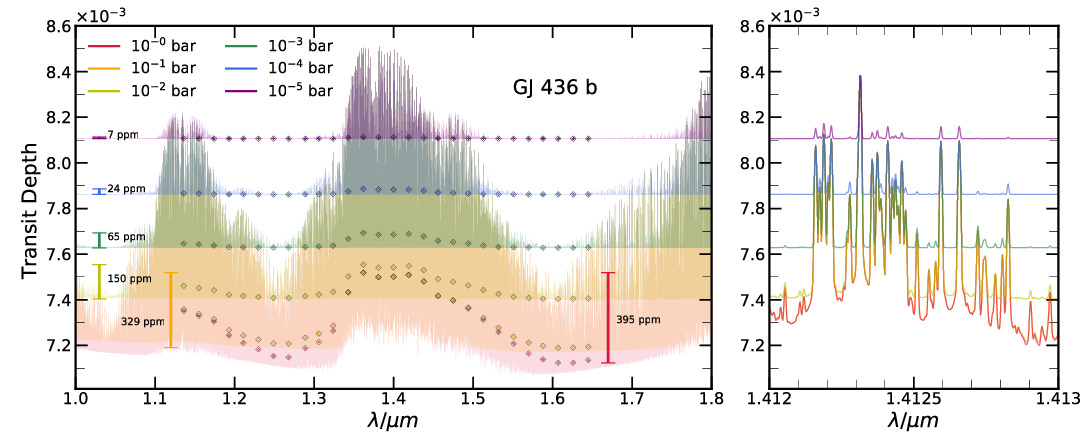

Recently, we have begun obtaining observations of warm Neptunes and super Earths, many of which show thick cloud cover in their atmosphere. These clouds obscure the atmospheric signal and make detecting species more difficult. However, high resolution (R > 20,000) ground based observations have the ability to probe a much wider range of altitudes, and thus potentially observe above the effects of clouds. My work has been to explore the detectability of species such as H2O, CH4, NH3 and CO by modelling two cloudy warm Neptunes, GJ 436 b and GJ 3470 b. The figure below shows the effect of clouds on observations. These features are present above the clouds and our calculations show H2O and the other species are potentially detectable even with quite thick clouds with just a few nights of observing time on a number of telescopes around the world. We also find that the Earth’s own atmosphere can potentially obscure detections of some species also present on the Earth, such as H2O. This work has recently been published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society and can be found here. A recent press release for this work can also be found here.